Originally published July 27, 2019

Last updated September 19, 2019

Posted in Ballarat, Featured, Gender & Sexuality, History & Culture, Law

Once upon a time there was a penal colony. The vast majority of convicts sent there were male. Sometimes, especially when they were in particularly confined or isolated conditions, they had sex with each other. So did a few women in the “female factories” (prisons). Captain Arthur Philip, the first Governor of the colony, said that those who commit sodomy should be sent to New Zealand to be eaten by the Maori.

Time passed. Soon there were fewer convicts, more gender balance, and just generally less criminality. We don’t have much record of homosexuality from the post-convict era. Though sodomy was still a crime punishable by death, there were very few convictions in the Australian courts, and of course nobody talked about it until Oscar Wilde and Freud.

And then, along came the twentieth century, with its sudden explosion of queerness! We will now proceed to spend the remaining 90% of this history of queer Australia on that period…

Take a quick look at Wikipedia’s article, LGBT history in Australia. It spends only five paragraphs (around 10% of the article) on the convict period, then jumps almost a century to 1932. SBS’s definitive timeline of LGBT rights in Australia skips straight from 1788 to 1901. Looking in the collections of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives, we see a similar scarcity of colonial material in their lists of theses and unpublished papers, papers presented at the Australian Homosexual Histories Conference, and this older bibliography dated 1999.

It’s true that same-sex attraction and sexual activity are hard to discern in the records of Australia’s colonial period, and for all the usual reasons: records of private activity are scarce, and when information makes it to the public sphere it’s usually because of a court case. This means that the only visible cases are the unhappy ones: the men arrested, charged, and convicted of sexual crimes. (Women, of course, are even less visible, in part because there was no law against them having sex with each other. Stories of people we might now identify as transgender are usually the result of a “scandal” occurring when the person’s birth sex is discovered.)

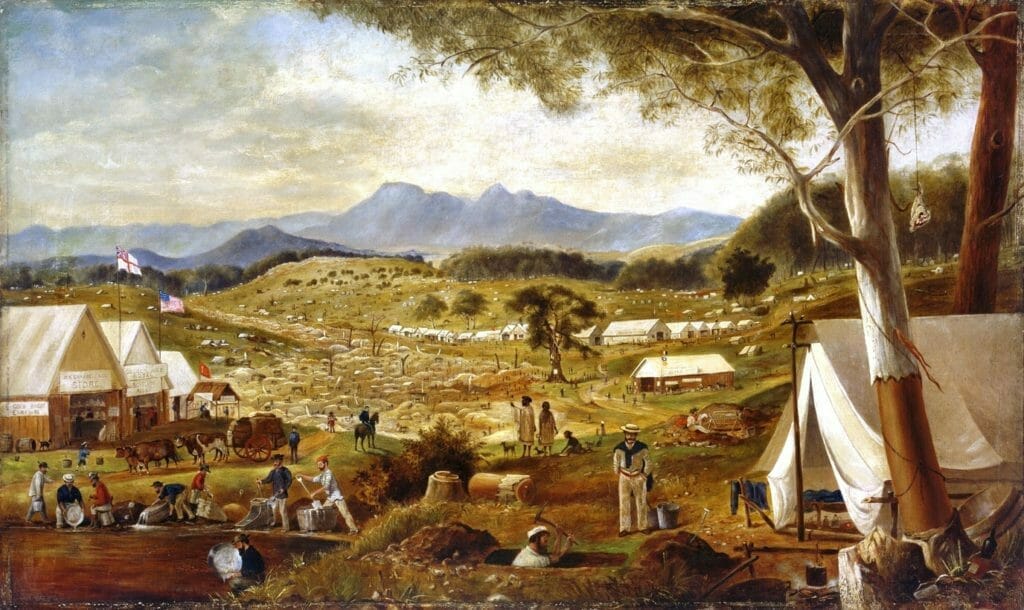

A simple search of Trove (the National Library of Australia’s digitised newspaper collection) for “sodomy” shows 732 results in total (accessed 26th July, 2019) for the colonial period across all of Australia, few of which seem to be part of our commonly-told story. While many of these are reprints of articles in multiple newspapers, there are still a wide variety of stories of our queer past. Even in my specific my area of interest, Ballarat and its surrounds during the gold rush period (1850-1880), there are 14 results (accessed 26th July, 2019) for “sodomy” in the local papers, although some refer to cases in Melbourne.

These results for “sodomy” in the colonial newspapers are far more numerous than most reviews of Australia’s queer history would seem to indicate, but they’re just the tip of the iceberg. We can actually discern a far wider breadth of queer history during the colonial period if we have an understanding of the language of the time, and how it’s used in the press.

I’m going to cover some of the main techniques I’ve used to dig up stories of sex between men (and other “queer” activity, such as cross-dressing) in Ballarat and the central Victorian goldfields ca. 1850-1880, using some of the euphemisms and less obvious terms common at the time. I hope that others interested in Australia’s queer history will be able to use the same techniques to find a wider variety of stories from the colonial period.

Sodomy in the Ballarat press

The crime of “sodomy” originated in English civil law, and hence in Australian colonial law, with Henry VIII’s Buggery Act of 1533, which outlawed “the detestable and abominable Vice of Buggery committed with mankind or beast.” Similar wording, albeit with the name of the crime shifting to “sodomy,” was adopted into the 1828 Offences Against the Person Act, which was the law in force in Victoria at the start of the gold rush.

As I noted above, prosecutions for sodomy (or attempted sodomy, a lesser charge) aren’t hard to find in the Ballarat newspapers during the gold rush period, simply by searching Trove for the word “sodomy.”

For example: on the 10th February 1860, before the Ballarat Circuit Court, “females having been recommended to leave the court” – something we’ll see repeatedly – John Singleton was charged with sodomy, pled “not guilty,” and was remanded. Nothing further is mentioned of this case in any Victorian paper that I can find.

In 17th October 1870, we see a report that Stephen Mettiger is on bail for sodomy. This is the only time the word “sodomy” is used in relation to this case, though it was widely reported over the course of some weeks using other language. It had been previously mentioned on the 5th October, and again on the 8th October, where his crime is described as an “unnatural offence,” as it was again at its conclusion on the 19th October.

In December 1871 we see a report of Ah Chen, alias Ah Munn, charged with sodomy. On the 29th February 1872, Ah Sam is convicted of attempted sodomy and sentenced to 6 years hard labour with three floggings.

On the 11th February 1874, John Gibson and Thomas O’Brian are brought before the circuit court for sodomy – the only case I’ve seen so far where two local men were charged together. Tracking the case through the papers, we see that although the Ballarat Star (linked above) reports it as “sodomy,” it’s reported in the Ballarat Courier on the same day as “a heinous offence.”

As the reporting of the case continues we start to see a range of language used. On the 12th, the Star mentions their case with the words “unnatural offence,” briefly on page two, and then in more detail on page four:

Unnatural Offence.— John Gibson and Thomas O’Brien were charged with having attempted to commit an offence of this description on the night of the 15th ult. Constable M’Guirk, stationed at Beaufort, and a contractor named George Murray, gave evidence, the particulars being unfit for publication. The jury found the prisoners guilty and they were remanded for sentence.

On the same day, The Ballarat Courier says the two men were “convicted of attempting a heinous offence at Stockyard Creek,” and again using their favourite language, report in more detail:

A Heinous Offence – John Gibson and Thomas O’Brien were placed in the dock charged with attempting to commit a heinous offence at Stockyard Hill on the 15th ultima. Both pleaded not guilty, and were undefended. The evidence of Constable M’Guirke and a contractor named Murray have been taken. The jury found the prisoners guilty, and they were removed to await sentence.

On the 13th, sentence was handed down, the same for both men: 7 years’ hard labour on the roads, with two floggings to be delivered in March and June. Both the Courier and the Star use the term “unnatural offence” in their reportage.

Knowing the right words

As we can see just from the reporting of the Gibson and O’Brien case, a variety of terms were used to describe sex between men in the local press, including “heinous offence” and “unnatural offence.”

When we widen our search of the newspapers to use these terms, we find far more cases. “Unnatural offence” and “unnatural crime” are by far the most productive that I’ve found.

- In 1860 at Yandoit, near Daylesford, the Star reports an “unnatural offence” case dismissed for lack of evidence.

- The case of the watchmaker’s dog arose in Redbank in the Pyrenees, northwest of Ballarat, in August 1862, and was reported in the Ballarat papers using the term “unnatural offence” and later “vicious habits” to describe an alleged attempted sexual act. (It was quite a saga, playing out in the courts over a couple of weeks, but in the end the defendant, Joseph Gregory, was acquitted and the complainant charged with perjury.)

- A correspondent from Smythesdale, to the south-west of Ballarat, writes in 1863: “hardly a week passes but what our morality is brought into question – indecent assaults, unnatural offences, and the like, being at the present time mostly in fashion.” (It’s possible, however, that some or all of the “unnatural offences” may have been bestiality in this case.)

- In 1876, the Ballarat Star reports that “Two cases of unnatural crime have been mentioned lately, men of good position in Melbourne being the culprits. Now we have a similar rumor as to a well-known resident of Geelong. The [Geelong] Advertiser says it is probable proceedings will be taken.” (Spoiler alert: no charges were laid.)

Although the Ballarat Courier’s favourite phrase “heinous offence” is common in the archives, it doesn’t only apply to sodomy. It was used for serious crimes such as rape and infanticide, but even more commonly it was used sarcastically, as for the crimes of selling ginger beer without a license or stepping off the footpath at the Botanical Gardens. However, there were a couple of examples of being used to refer to male/male sex, specifically sexual abuse of boys.

- In Melbourne in 1866, an early report of institutional child sexual abuse in “industrial schools,” including one at Sunbury in Melbourne’s western suburbs, described “heinous offences” against both girls and boys.

- In 1870, a Ballarat Courier editorial on penal discipline mentions the death penalty for “the more heinous offence” (as compared to sexual assault on a girl – in other words, sexual assault on a boy).

The term “gross indecency,” which became famous in UK law with the 1885 “Labouchere Amendment,” shows up quite often before that date in the Ballarat papers. It’s used for a variety of sexual crimes, but at least some of them refer to sex between men:

- In 1864, the judge in what appears to have been an attempted sodomy case found that there was insufficient grounds for prosecution, but that “An act of gross indecency seemed to have been committed, and the police could still prefer an accusation for a common assault.”

- In 1869, an editorial clearly uses the term to refer to sex between men:

Then for rape upon women and children the lash should be absolutely certain, as well as for all cases of gross indecency. This is the more necessary now that the capital sentence has been virtually abolished, and a consequent looseness fallen upon the administration of justice in relation to these crimes.

Searching for “indecency” alone also gives us a great many stories, albeit mixed in with a lot of false positives for things like public nudity, urination, indecent assault on women, etc. In indecency cases, it’s sometimes necessary to read between the lines to pick up hints that a case might relate to queer sex.

In one such case in Melbourne, a case against a Russian or Polish man named Albert Klaperode was dismissed “on account of the Crown being unable to find the chief witness.” Missing witnesses were a common feature of sodomy cases, as the witness – probably the other party to the queer sex act – may have initially agreed to testify in exchange for not being charged, and then taken off for parts unknown before the trial.

Klaperode is also interesting for having been charged multiple times with sodomy or related offences, and for the language used in the Melbourne papers to describe the crimes: in one case “attempt to commit a felony” and in another case in 1874, “assault with intent.” These terms are so vague as to be useless for searching, and leave us wondering what other queer crimes might be hidden under such inoccuous language. The only way I found these was by searching more widely for his name, after reading:

Inspector Kabat mentioned that the prisoner had been twice sentenced to be hung for the same offence, once in New Zealand, and again in Geelong: but he could not account for the man’s being at liberty.

Unfit for publication

Language such as “unfit for publication” or “recommended/ordered to leave the court” show up regularly in reports of sex between men. The censorship of information about these topics can, counter-intuitively, be used to find relevant articles.

- In 1859 the Mount Alexander Mail reports an “unnatural crime” (sexual assault by an older man on a 14 year old boy) committed by John Flannery at Talbot, northwest of Ballarat. “The particulars are in parts wholly unfit for publication, but sufficient of the evidence is given to convey some idea of a detestable night of depravity upon the part of a brute in human shape.” If there was such a thing as 19th century clickbait, this would be it.

- In an 1864 bestiality case against one Jamie Chisworth, “Women and children were ordered to leave the court, but a lot of youths were permitted to remain and hear the disgusting details of the case.”

- In an unusual case of sodomy between a man and a woman, “James Wilson was charged, first with rape, and secondly with the commission of an unnatural offence. The case was heard with closed doors, and the evidence of the prosecutrix, a married woman named Catherine M’Intyre, and of Dr Creclinan having been taken, the Bench dismissed the first charge on the grounds that prosecutrix had been a consenting party ; and committed the prisoner for trial at the next Circuit Court at Ballarat on the second charge.”

The same language was also used for a wide variety of other sexual offences. One such article about a sexual assault on a ten year old girl by a man named Michael Jordan gives some indication of how the judiciary and the press worked together to suppress the details of sexual cases:

This case was heard with closed doors, the magistrate observing that be had no objection to seeing the gentlemen of the press remain in court, but if they published any of the disgusting details of the evidence he would exercise his power by not allowing them to be present on a like occasion in future.

Words for gender nonconformity

Just as the language for homosexuality has changed, so has that for gender nonconformity, such as crossdressing or people who lived as a gender other than that assigned at birth. Stories about men in women’s clothes, or women in men’s clothes, can be found by searching for terms like “personating a woman,” “personating a man,” “man-woman,” or “female husband.” Even the terms “in male attire” or “in female attire” can be productive.

It’s hard to describe these stories in terms we understand, as they tend to straddle a difficult space between crossdressing for practical or entertainment purposes, what we would consider transgender identities, queer performativity, and same-sex acts.

A description of a Melbourne sex worker, Ellen Maguire (alias John Wilson), says:

The man, Maguire was brought up to-day at the Fitzroy Court charged with personating a woman. The evidence was altogether unfit for publication. He was committed for trial. It appears this disgusting individual had been in the various colonies, and had carried on a system of deception of the most revolting nature without detection for several years.

Edward De Lacy Evans, who lived as a man on the goldfields for decades before being discovered to have been born Ellen Tremayne, is described in the papers as “The Man-Woman Evans” and reported as “An Extraordinary Personation Case.”

Some crossdressing cases became so well known that the names of the accused can themselves be used as search terms. Much as men in late 19th or early 20th century might be referred to as “the Oscar Wilde type,” newspapers in the colonial period would make reference to other well known cases such as Boulton and Park, or Edward De Lacy Evans to hint at queer goings on. For instance, De Lacy Evans is described in the Queensland press in comparison to Boulton and Park:

Extraordinary disclosures have, been made regarding the female lunatic discovered in male attire. The Boulton and Park case was, in fact, much less remarkable. Probably no greater or more successful piece of imposition has ever been recorded.

The St. George Standard and Balonne Advertiser, 27th September, 1879

In 1872, the inquest into a suicide pact gone awry in Melbourne’s Treasury gardens, between Edward Feeney and Charles Marks, led the Geelong Advertiser to say:

The Argus says:—” A number of letters were, put in evidence, and there were statements made by the medical witness which went to confirm the interpretation that many had put upon the behavior of the two men.” The Telegraph less vaguely observes that “The medical evidence was of a horrible character, and only paralleled by that given in the Boulton and Park trial.”

(The Boulton and Park trial had included medical evidence of anal penetration as part of its proceedings.)

Another article just prior to Feeney’s hanging said:

Since his imprisonment he has frequently spoken disparagingly of Marks, who had often been troublesome to him owing to his expressions of fondness and endearment. Feeney further stated that Marks had continually boasted of an intimacy with Park and Boulton, of London notoriety.

Searching for obscure and euphemistic terms can often lead you on a circuitous route to more stories. When I was searching for “Boulton and Park” I found the Treasury Gardens suicide pact mentioned above; reading more on that case I found an adjacent article containing a notice of prosecution for “Unnatural offences” against a person the OCR named as “Albert C. rClapetd,” but was in fact the same “Albert Klaperode” mentioned above as a repeat offender whose crimes were seldom mentioned in terms clear enough to search for. It was only by searching for references to Boulton and Park, a London case, that I came across another mention of this Ballarat offender. (For more on the problems of OCR, see below.)

The British connection

It’s not surprising that Australian papers referred to British cases such as the Boulton and Park one. Australia was very closely connected to Britain during the colonial period. There was considerable mobility between the UK and its colonies. It wasn’t just miners coming here for the gold rush, but everyone from religious evangelists to entertainers to journalists. Ideas were shared via telegram and letter, and constantly reported in newspapers.

This means that the language used about homosexual acts was largely shared between Britain and Australia. Anyone interested in the queer history of Australia in the 19th century can learn a lot from reading British queer history of the same period.

Charles Upchurch’s work in “Before Wilde: Sex Between Men in Britain’s Age of Reform” (and elsewhere) is a good resource, as are H. G. Cocks’ “Nameless Offences” and Graham Robb’s “Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century,” all of which extensively cover court cases during the 19th century. Rictor Norton’s work on queer culture before Wilde, especially “The Myth of the Modern Homosexual: Queer History and the Search for Cultural Unity,” gives more insight into the language associated with male/male sex and other queer acts and identities.

In researching “Before Wilde,” Upchurch used archives of the Times and other British newspapers. He searched through both human-curated indexes to the Times and full-text digital archives, and found that the results varied. His paper on this, “Full-Text Databases and Historical Research: Cautionary Results from a Ten-Year Study,” lists some of the terms he used in his searches, including: sodomy, abominable crime, unnatural crime, gross indecency (which Upchurch found to be seldom relevant prior to 1885’s Labouchere Amendment), unnatural offence, unnatural crime, infamous crime, infamous assault, indecent assault (which turned out to be the most productive term for him), and indecent conduct to name just a few.

A number of terms turned out to be useful to Upchurch when searching a human-curated index, but resulted in a large number of false positives in the full text search. These included searches for bare adjectives such as “abominable,” “infamous,” “detestable,” and “nameless,” and terms such as “for misconduct” and “for misbehaviour” which were occasionally used euphemistically to shield high-profile defendents in sodomy cases.

I found Upchurch’s work after I had already spent considerable time in Trove’s newspaper archives, but it’s interesting to see the similarities in terminology between Australian and UK newspapers. A good understanding of British queer history during the 19th century is extremely relevant to understanding Australia’s queer history during the same period.

The downside of full-text digital search

Upchurch’s experiences in the archives highlight some of the problems of looking for queer history in full text digital archives. The searchability that gives us ready access to so many stories also obscures them in a morass of irrelevant material, while optical character recognition (OCR) on old newspapers is often inaccurate, meaning that many more stories are probably missing from the results.

Upchurch suggests a potential remedy: a cooperative database of queer stories in the historical press. The NLA’s Trove supports this, in part, by permitting “tagging” by volunteers. Some of Trove’s newspaper articles are already tagged with “homosexuality” and other relevant terms, though this is far from complete: at the time of writing (26th July, 2019), only 335 articles in the corpus were tagged “homosexuality,” and support for tag searching in the advanced search is limited.

However, while Upchurch comments that “there is a pervasive misconception that the new electronic databases make recovering information about sex between men in the public sphere easy and straightforward,” I have to say that this is where I perceive a difference between the UK and Australia. Many may be happily wallowing in Britain’s 19th century digital archives (with varying degrees of success, as the recent criticism of Naomi Wolf’s book “Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love” shows), but fewer queer historians in Australia seem to be digging through ours, especially in regional areas.

There is clearly a lot more research to be done on the period between the decline of convict transportation and Federation. I hope that this article will give anyone who’s interested some useful tools and terminology to go digging in Trove, despite its drawbacks, and unearth yet more stories of Australia’s queer colonial history.

References

Newspaper reports, sorted by year and defendant/topic

1859, John Flannery

- “HORRIBLE CASE OF UNNATURAL CRIME AT THE BACK CREEK.” Mount Alexander Mail (Vic. : 1854 – 1917). April 15, 1859. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199052346.

1860, John Singleton

- “BALLARAT CIRCUIT COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). February 11, 1860. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72464933.

1860, unnamed defendant, at Yandoit

- “YANDOIT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). December 7, 1860. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66336178.

1861, James Wilson

- “LEARMONTH POLICE COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). April 5, 1861. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66338371.

1862, Joseph Gregory

- “NEWS AND NOTES.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). September 2, 1862. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66326854.

- “REDBANK.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). August 20, 1862. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66326499.

1863, John Wilson alias Ellen Maguire

- “LATEST NEWS.” Mount Alexander Mail (Vic. : 1854 – 1917). October 20, 1863. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article200380517.

1863, at Smythesdale

- “NEWS AND NOTES.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). March 2, 1863. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72555263.

1864, Jamie Chisworth

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). July 21, 1864. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66346609.

1866, Michael Jordan

- “POLICE.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). July 27, 1866. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112863837.

1868-1874, Albert Klaperode

- “No Title.” Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 – 1954). July 14, 1868. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article244960170.

- “MELBOURNE CRIMINAL SESSIONS.” Leader (Melbourne, Vic. : 1862 – 1918, 1935). August 22, 1868. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197427012.

- “POLICE INTELLIGENCE.” Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954). March 7, 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197448980.

- “GENERAL SESSIONS.” Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 – 1954). November 28, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article244337178.

1870, Stephen Mettiger

- “EASTERN POLICE COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). October 5, 1861. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66342533.

- “EASTERN POLICE COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). October 8, 1861. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66342575.

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). October 17, 1861. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66342837.

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). October 19, 1861. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66342872.

1870, on penal discipline

- “No Title.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 23, 1870. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article191567725.

1871, Ah Chen alias Ah Munn

- “BALLARAT GENERAL SESSIONS.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). December 12, 1871. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article191427512.

1872, Ah Sam

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). February 29, 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197627054.

1872, Edward Feeney and Charles Marks

- “EXECUTION OF FEENEY.” Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954). May 15, 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197446400.

- “TOWN TALK.” Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1859 – 1929). March 9, 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article150417693.

1874, John Gibson and Thomas O’Brien

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). February 11, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201971469.

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 11, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article192284990.

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). February 12, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201971504.

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 12, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article192286527.

- “NEWS AND NOTES.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). February 12, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201971516.

- “No Title.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 12, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article192286533.

- “CIRCUIT COURT. Thursday, 12th February.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). February 13, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article201971538.

- “No Title.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 13, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article192285989.

- “CIRCUIT COURT.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 13, 1874. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article192285968.

1876, rumours at Geelong

- “NEWS AND NOTES.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). September 23, 1876. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article199831002.

- “TOWN TALK.” Geelong Advertiser (Vic. : 1859 – 1929). September 25, 1876. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article150635074.

1879, Edward De Lacy Evans

- “THE EXTRAORDINARY PERSONATION CASE.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). September 5, 1879. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article232145630.

- “THE MAN-WOMAN EVANS.” Gippsland Times (Vic. : 1861 – 1954). September 10, 1879. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62028400.

- “A WOMAN WITH THREE WIVES.” St. George Standard and Balonne Advertiser (Qld. : 1878 – 1879; 1902 – 1904). September 27, 1879. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article212733059.

Various dates, uses of “gross indecency”:

- “EASTERN POLICE COURT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). August 13, 1864. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66347244.

- “NEWS AND NOTES.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). March 2, 1867. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112873242.

- “The Ballarat Star.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). August 23, 1869. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112891751.

- “POLICE.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). November 22, 1871. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197574335.

- “POLICE.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). May 4, 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197628510.

- “MELBOURNE.” Ballarat Star (Vic. : 1865 – 1924). December 4, 1882. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article202700316.

Various dates, uses of “heinous offence”:

- “DISTRICT COURT.” Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954). November 6, 1857. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article154831960.

- “No Title.” Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954). September 21, 1864. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155016412.

- “THE BOTANICAL GARDENS.—ANOTHER COMPLAINT.” Star (Ballarat, Vic. : 1855 – 1864). December 17, 1864. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66350581.

- “FRIGHTFUL IMMORALITY AT THE INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS.” Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954). March 31, 1866. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155047127.

- “INFANTICIDE.” Telegraph, St Kilda, Prahran and South Yarra Guardian (Vic. : 1864 – 1888). August 3, 1867. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108125598.

- “No Title.” Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1869 – 1883; 1914 – 1918). February 23, 1870. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article191567725.

Other

“Australian Homosexual Histories Conference: A List of Papers and Presentations.” Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives, 2014. https://alga.org.au/files/AHH-papers.pdf (accessed July 26, 2019).

“Australian Lesbian and Gay History: A Bibliography.” Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives, 1999. https://www.alga.org.au/files/bibliography.pdf (accessed July 26, 2019).

The Statutes at Large, of England and of Great Britain :From Magna Carta to the Union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland. London :, 1811. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101075729275.

Cocks, Harry G. Nameless Offences: Homosexual Desire in the 19th Century. London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Lea, Richard. “Naomi Wolf Admits Blunder over Victorians and Sodomy Executions.” The Guardian, May 24, 2019, sec. Books. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/may/24/naomi-wolf-admits-blunder-over-victorians-and-sodomy-executions (accessed July 26, 2019).

Norton, Rictor. The Myth of the Modern Homosexual: Queer History and the Search for Cultural Unity. Washington, 1997.

Robb, Graham. Strangers: Homosexual Love in the 19th Century. Picador, 2004.

Upchurch, Charles. Before Wilde: Sex between Men in Britain’s Age of Reform. University of California Press, 2013.

Upchurch, Charles. “Full-Text Databases and Historical Research: Cautionary Results from a Ten-Year Study.” Journal of Social History 46, no. 1 (September 1, 2012): 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shs035.

Wikipedia contributors, “Australian gold rushes,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Australian_gold_rushes&oldid=906351808 (accessed July 26, 2019).

Wikipedia contributors, “LGBT history in Australia,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=LGBT_history_in_Australia&oldid=891798365 (accessed July 26, 2019).

Winsor, Ben. “A Definitive Timeline of LGBT+ Rights in Australia | SBS Sexuality.” SBS, November 15, 2017. https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/sexuality/agenda/article/2016/08/12/definitive-timeline-lgbt-rights-australia (accessed July 26, 2019).

Wolf, Naomi. Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love, 2019.

Support my work

Hi, I'm Alex. I'm an independent researcher, writer, educator and activist based in Ballarat, Australia. If you appreciate my work, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon. Even $1 a month helps!

Not only will you help me do more work like this, but you'll also get regular updates and sneak peeks at my work in progress.

Hi Alex

A fascinating article. Did you know that the Public Record Office Victoria holds public records relating to criminal trials etc? These are the original documents, not newspaper reports. Basically, there is more to it that a Trove search!

The search string below gives you an idea of what our collection holds. (use the beta version of the website to better search results!)

https://beta.prov.vic.gov.au/search_journey/select?keywords=sodomy&iud=true

If not already digitised and online (which is unlikely given the nature of the records), they can be ordered and view in our reading rooms here in North Melbourne or at the Eureka Centre in Ballarat – see oue ‘contact us’ page for details.

Thank you, David! I’ve had a bit of a hunt around in the PROV records and talked to some people there, but it seems the relevant court records only record the defendant’s name, charge, conviction and sentence and not any juicy details or transcripts of the court proceedings. Of course that’s what I’d really like to see, especially for the ones that were “unfit to publish”. So, sadly, in many ways the PROV records are less help than the papers, though in a few cases (eg. where reporting of a case trails off and I can’t find the outcome) it could be useful.

That’s a shame Alex! But I’m pleased that you were aware of PROV and had a look see.

Cheers

David