Originally published June 6, 2019

Last updated July 27, 2019

Description

Ballarat queer history display in the form of six pull-up banners, originally created for Ballarat Heritage Weekend, May 25th-26th, 2019.

Project type

Topics

19th century, 20th century, AIDS, Ballarat, Ballarat Community Health, Captain Moonlite, Edward De Lacy Evans, Gay Liberation, Gender, History, Homophobia, Immigration, Local History, Marriage Equality, Monte Punshon, Sexuality, World War II

About the display

I was contracted by Ballarat Frolic Festival (a regional LGBTQ+ arts and culture festival) to prepare and design a visual display of Ballarat’s queer history for Ballarat Heritage Weekend, 25th-26th May 2019. This was the first time Ballarat Frolic Festival had been involved in Heritage Weekend, and is part of their broader outreach program to engage with Ballarat’s wider community.

As I was already working on the Ballarat Queer History Tour, covering the colonial/gold rush period, we were able to provide information for the first two panels. The Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives provided copies of newsletters and other relevant materials from the 1990s-2000s, while Ballarat Frolic Festival’s community provided photos for the marriage equality section on the last panel.

I undertook independent research to find examples of Ballarat’s queer history from 1900 to the mid 1990s, through newspaper archives, secondary sources (particularly around World War II), the press scrapbooks kept by Ballarat Community health, and interviews with older members of the community who had worked in AIDS prevention in the 1980s to early 90s.

The display was designed to be printed on six pull-up banners, forming a pride rainbow. These were displayed in the council committee rooms in Ballarat Town Hall during Heritage Weekend, alongside printed copies of LGBTQIA+ community newsletters from the 1990s, attracting over 600 viewers. The display will be re-used by Ballarat Frolic Festival for future events.

Full Text Transcript

(Note: minor errors have been corrected.)

Panel 1: 1850-1900

We Have Always Been Here: Celebrating Ballarat’s LGBTQIA+ History

Early History

Ballarat sits on the land of the Wadawarrung and Dja Dja Warrung people, which was colonised by the British in the 19th century. The discovery of gold in 1851 brought many immigrants who soon displaced the original owners. Along with military force, mining, agriculture, and diseases, the British brought their laws against homosexuality. Although we know little about indigenous sexuality prior to colonisation, LGBTQIA+ Aboriginal people existed and remained in the Ballarat region, and are part of our community today.

In the colonial courts

In the colonial period, words such as “homosexual” and “transgender” didn’t exist. The term for sex between men was “sodomy”, which was punishable under law by death or life imprisonment. Fortunately, standards of evidence were strict, and it was difficult to obtain a conviction. There were no laws against sex between women.

Unnatural Offence.— John Gibson and Thomas O’Brien were charged with having attempted to commit an offence of this description on the night of the 15th ult. Constable M’Guirk, stationed at Beaufort, and a contractor named George Murray, gave evidence, the particulars being unfit for publication. The jury found the prisoners guilty and they were remanded for sentence.

Ballarat Star, 1874

Among the Chinese community, homosexuality was not taboo as it was in British society. White writers talking about the Chinese immigration often mentioned their propensity for polygamy and “worse vices”. There are a number of records of sodomy cases involving Chinese immigrants in Ballarat.

Edward de Lacy Evans

EXTRAORDINARY CASE OF CONCEALMENT OF SEX

A woman, under the name of Edward De Lacy Evans, has for 20 years passed for a man in various parts of the colony of Victoria… As it is almost impossible to give an account of the case without making use of the masculine pronoun when referring to Evans, we propose to use that appellation…

Bendigo Advertiser, 1879

On the goldfields some women dressed as men. We might now call them transgender. One of the most famous of these was Edward de Lacy Evans, from Bendigo, who was the centre of a scandal in 1879. Evans became ill and was committed to an asylum, where he was forced to be stripped and washed. That’s it was discovered that Evans had been born with female sex organs.

The fellers there took hold o’ me to give me a bath, an’ they stripped me to put me in the water, an’ then they saw the mistake. One feller ran off as if he was frightened; the others looked thunderstruck an’ couldn’t speak. I was handed over to the women, and they dressed me up in frocks and petticoats.

Panel 2: 1869-1880

Captain Moonlite, Ballarat’s Gay Bushranger

Bank Robbery at Mount Egerton

Captain Moonlite (Andrew Scott) was a bush ranger who moved seamlessly between the upper and lower echelons of 19th century society. He was hanged for his crimes in 1880 while mourning his partner James Nesbitt.

Born in Ireland, Scott’s parents wanted him to join the priesthood. When he arrived in Victoria he was appointed as a lay reader in the Anglican church, and was sent to Mt. Egerton, 30km east of Ballarat.

On 8 May 1869, a masked man held up the bank at Mount Egerton. A young banker whom Scott had befriended, Ludwig Julius Wilhelm Bruun, told authorities that a masked man had forced him to open the bank’s safe and hand over its gold. The intruder left a note:

I hereby certify that LW Bruun has done everything within his power to withstand this intrusion and the taking of money which was done with firearms.

(signed) Captain Moonlite.

As a criminal, Scott was more urban hustler than highwayman. He was handsome and athletic, and was a skilled rider and crack shot. The name of Captain Moonlite with its irresistible hint of midnight romance, took on a life of its own in the media. His attempted escape from Ballarat Gaol further popularised his reputation.

A journalist described him as:

Brave to the verge of recklessness, cool, clear-headed and sagacious, and with a certain chivalrous dash, he is the beau ideal of a brigand chief.

Scott and Nesbitt

Scott was captured and imprisoned in Ballarat Gaol, from which he soon escaped by tunnelling out of his cell and using tied-together blankets to scale the walls. Recaptured, he was imprisoned in Pentridge Prison, Melbourne, where he met James Nesbitt.

Together with four other men, they formed a gang and continued a life of crime. Troopers captured them at Wantabadgery, NSW (pictured below). Nesbitt tried to lead the troopers away from the homestead so that Scott could escape, but was shot.

His leader wept over him like a child, laid his head upon his breast, and kissed him passionately.

Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 1894

While in prison awaiting his hanging Scott wrote to Nesbitt’s mother:

Nesbitt and I were united by every tie which could bind human friendship. We were one in hopes, one in heart and soul and this unity lasted until he died in my arms.

Awaiting execution, Scott wore a ring made from Nesbitt’s hair, and pleaded with his gaolers to bury him with the younger man in the graveyard at Gundagai.

There is still debate over the exact nature of Scott and Nesbitt’s relationship, but there is no doubt that they shared an intense love for each other.

I long to join him where there will be no more parting.

His request was denied. However, in 1995 a group of Scott’s admirers persuaded the government to surrender Moonlite’s body to be re-interred in the Gundagai cemetery.

Panel 3: 1900-1945

A New Century: Social Change and World Wars

Mannish Women and Effeminate Men

The 20th century saw a new awareness, if not always acceptance, of homosexuality. The word “homosexual” first appeared in English in 1892. Oscar Wilde’s trial in 1895 for “gross indecency” was widely reported in newspapers worldwide.

By the 1920s, a gay subculture was emerging both in Melbourne and Ballarat, with identifiably queer young men visible in the streets and occasionally in the courts.

For women, the campaign for women’s suffrage and the fashions of the 1920s gave them greater independence and allowed them to dress and associate as they wished.

Another section of the new society-women of the period is accused of eschewing matrimony, and of exhibiting a strong desire to escape, as far as possible, from the trammels imposed upon her bythe accident of her sex. This sort of “man-woman”, we are told, is masculine in her voice, *her stride, her manners and her attire.

The Ballarat Star, 1908

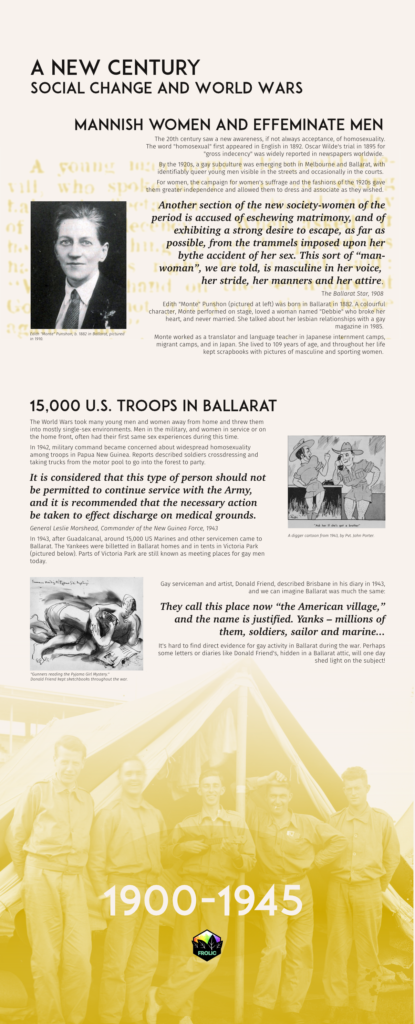

Edith “Monte” Punshon (pictured at left) was born in Ballarat in 1882. A colourful character, Monte performed on stage, loved a woman named “Debbie” who broke her heart, and never married. She talked about her lesbian relationships with a gay magazine in 1985.

Monte worked as a translator and language teacher in Japanese internment camps, migrant camps, and in Japan. She lived to 107 years of age, and throughout her life kept scrapbooks with pictures of masculine and sporting women.

15,000 U.S. Troops in Ballarat

The World Wars took many young men and women away from home and threw them into mostly single-sex environments. Men in the military, and women in service or on the home front, often had their first same sex experiences during this time.

In 1942, military command became concerned about widespread homosexuality among troops in Papua New Guinea. Reports described soldiers crossdressing and taking trucks from the motor pool to go into the forest to party.

It is considered that this type of person should not be permitted to continue service with the Army, and it is recommended that the necessary action be taken to effect discharge on medical grounds.

General Leslie Morshead, Commander of the New Guinea Force, 1943

In 1943, after Guadalcanal, around 15,000 US Marines and other servicemen came to Ballarat. The Yankees were billetted in Ballarat homes and in tents in Victoria Park (pictured below). Parts of Victoria Park are still known as meeting places for gay men today.

Gay serviceman and artist, Donald Friend, described Brisbane in his diary in 1943, and we can imagine Ballarat was much the same:

They call this place now “the American village,” and the name is justified. Yanks – millions of them, soldiers, sailor and marine…

It’s hard to find direct evidence for gay activity in Ballarat during the war. Perhaps some letters or diaries like Donald Friend’s, hidden in a Ballarat attic, will one day shed light on the subject!

Panel 4: 1970-1990

Liberation and Crisis: Advocating for Change, Facing AIDS

Rights for Homosexuals

In the 1970s, the fight began for gay rights, in particular the decriminalisation of homosexuality (which occurred in Victoria in 1980). Ballarat residents participated in Melbourne activist groups such as CAMP and Society Five, travelling back and forth to attend meeting and protests.

Social Groups

For gay men living in Ballarat, their social life was underground, often conducted in private homes. A circuit of dinner parties was attended by the better-off gay men, with high standards of catering expected of the hosts. There were also support groups, which were less exclusive.

One local man recalls:

I saw an ad in the Courier. You had to write to them. They rang me and invited me to someone’s house for a meeting. When I showed up, there were a group of men all sitting around and drinking tea. They weren’t too sure of me at first, but eventually they decided I was okay. That was when they all reached behind their chairs and took out their knitting.

Although there were no gay bars or clubs in Ballarat, some men met in public places. One of these was the site of the old Civic Baths on Armstrong Street (now the location of BADAC), which in turn were built on the site of Turkish baths which dated back to the Gold Rush period. Although the baths were condemned and boarded up, gay men still met there into the 1980s, as they no doubt had when it was the old Turkish Baths – an extraordinary example of continuous use by the community.

The AIDS Crisis

The first diagnosed AIDS case in Australia was in 1982. AIDS quickly became a major focus for the gay community. Ballarat’s response was led by Ballarat Community Health, which opened its Sexual Health Clinic in 1989. They also offered counselling, coordinated home care, and sent safer sex educators out to schools.

A former Ballarat Community Health staff member recalls:

We were known as the sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll organisation of community health because we had the sexual health clinic, we had the needle exchange…

The Ballarat and District AIDS Working Party (pictured below, in costume for the Begonia Festival parade) brought together people from several local organisations.

However, ignorance and stigma were rife. There were protests outside the Ballarat Base Hospital by men who did not want their wives caring for men with AIDS. *A researcher who surveyed Ballarat residents about their knowledge of the virus received written and verbal abuse, and some people refused to even touch the survey.

Treatments for HIV/AIDS became available in the late 80s, and more effective combination treatments in the mid 1990s. Modern medication can prevent HIV or bring existing infections to an undetectable level, which prevents transmission.

Panel 5: 1990-2010

Clubs and Community: Ballarat Comes Out of the Closet

Bars and Clubs

The 1990s saw the establishment of Ballarat’s first specifically gay venues and events, such as the Provincial Hotel which welcomed the gay community on Sunday afternoons and the Camp Hotel, located where Irish Murphy’s is now, holding a gay night once a week. Other venues included The Mallow Hotel (Cafe Pucci), The Rat (Bridge Mall Inn), Craigs Hotel (The Basement), Grainery Lane Theatre and Porters (Freight Bar).

Groups such as the Ballarat and District Gay Society (BADGS), bGlad, bBent and Gabrielle’s Place (for lesbians) were founded during this time. These groups ran coffee afternoons, walking groups, art and craft get togethers, formal dinners, art exhibitions and dances.

Community members still talk about events during this period, such as Pouffes and Liqueurs, Spuds, the Hairspray party, and drag queens partying at the Town Hall on the millennium.

News and Views

Newsletters for the community groups didn’t just announce events. Before social media, they were an important way to stay abreast of what was going on in the scene. They also provided relevant news reprinted from other publications, views and editorial, regular columnists, and even community gossip.

Amusing to watch the various blossomings of romance at the Tigertown dance. One young Ballarat lad’s loving was cut a trifle short when he had to board the bus to go home. Unfortunately, he found it impossible to convince the tree, around which he had kept his arms all evening, to board the bus with him!

The Tattler, April 1991

The newsletters also reported on homophobic violence that seemed to reach epidemic proportions at the peak of the AIDS crisis, reporting on incidents and advising community members of what to do if it happened to them.

Panel 6: 2010-Present

Marriage Equality and Beyond: Life in the 21st Century

Toward Equality

Since the early 2000s, Ballarat’s LGBTQIA+ community has seen steadily increasing support.

Zaque, a group for LGBT+ youth, was originally created by the City of Ballarat in 2004. In 2009, Koby Bunney founded Equal Love Ballarat, which campaigns for equal rights. Their pro-marriage-equality march in 2010 was the first of its kind in regional Victoria.

Local Labor MP Catherine King pledged to support the LGBTQIA+ community in 2013, and the City of Ballarat followed with a “No to Homophobia” measure in 2014. The City, along with a number of other institutions, started to fly the pride flag for IDAHOBIT Day (May 17th) in 2016.

However, the council’s support has not always been there. During the Marriage Equality Survey, in a very contentious council meeting, the council voted not to fly the rainbow flag in support of the LGBTQIA+ community. It was eventually displayed around the town hall after the community voted “Yes”.

Ballarat Says Yes!

In 2017 the federal government’s Marriage Survey asked the country to vote on marriage equality for people of all genders. Ballarat voted overwhelmingly in favour, with 71% voting “Yes” – the 24th highest vote out of 154 electorates, with a national average of 62%.

Ballarat Pride Hub, established the same year, was the centre of Ballarat’s “Yes” campaign. Local advocates led an active campaign, working tirelessly to raise awareness and gather support from the community.

A Diverse Community

Ballarat’s Frolic Festival also launched in 2017, offering an annual festival of LGBTQ+ arts and culture. The festival continues each November, offering a broad range of activities to serve Ballarat’s diverse community.

In 2019, it was announced that Ballarat Community Health would become host to the state’s first regional gender centre, serving the trans and gender diverse community. Ballarat also hosts a number of trans and gender diverse support and social groups.

Ballarat is now home to many LGBTQIA+ groups and a growing and diverse community who come together for mutual support, celebration, activities, and advocacy.

Thanks to

This display was prepared by Ballarat Frolic Festival with the assistance of:

- Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives

- Ballarat Community Health

- Ballarat Courier

- Alex Bayley

- Warren Bowen

- Koby Bunney

- Tom Hodgson

- Alex Serrurier

- David Waldron

- Rick Youssef

For more information, contact info@frolicfestival.org.